It seems a given that humanity universally desires a long life, which aligns with our powerful survival instincts. Some people want it more than others. What prompted me to think about this is a new Netflix documentary. There are countless articles about how to live a long life, but the more important question is seldom answered: Why would you want to?

Don't Die: The Man Who Wants to Live Forever

Consider Bryan Johnson. He’s a 47-year-old tech entrepreneur, who is the subject of the Netflix documentary Don't Die: The Man Who Wants to Live Forever, which premiered on January 1, 2025. I have not watched it and don’t intend to. I have, however, read about it.

Johnson has gained attention for his extensive and costly anti-aging regimen, known as Project Blueprint, through which he aims to reverse the aging process and significantly extend his lifespan. His daily routine includes taking over 50 pills, adhering to a strict diet, undergoing various medical treatments such as gene therapy, plasma transfusions, and fat injections, and spending millions of dollars annually on these efforts.

If his medically unapproved pill popping doesn’t harm him, his exercise and diet routine will at least give him a chance at a higher quality of life and maybe a somewhat longer life, as it will for anyone. But Methuselah long? I and a lot of other people are skeptical.

Why I Hope to Die at 75 - Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel

At the opposite side of the discussion is Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, a bioethicist and oncologist. He wrote a provocative essay for The Atlantic in 2014 titled Why I Hope to Die at 75. In the piece, he argued that living beyond 75 often involves a decline in health, productivity, and quality of life, and that he personally wished to avoid this phase of life.

“I am sure of my position. Doubtless, death is a loss. It deprives us of experiences and milestones, of time spent with our spouse and children. In short, it deprives us of all the things we value.

But here is a simple truth that many of us seem to resist: living too long is also a loss. It renders many of us, if not disabled, then faltering and declining, a state that may not be worse than death but is nonetheless deprived. It robs us of our creativity and ability to contribute to work, society, the world. It transforms how people experience us, relate to us, and, most important, remember us. We are no longer remembered as vibrant and engaged but as feeble, ineffectual, even pathetic.”

Emanuel stresses that he has no plans to die by suicide. He simply maintains that after age 75, he will not accept any medical treatment that would prolong his life. He wrote the article when he was 57 and he is still only 67 today but says he has not changed his mind.

Granted, Emanuel’s position is extreme, but he is not the only one who has ever held that position.

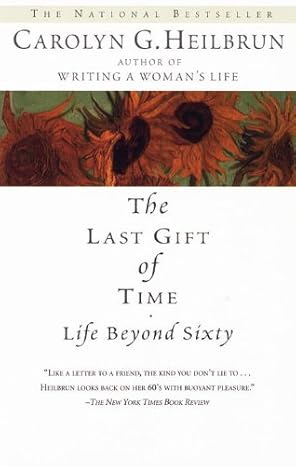

The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty

Gayle G. Heilbrun was a prominent feminist scholar and author of several works, including scholarly and fictional writings under the pseudonym Amanda Cross.

In her book, The Last Gift of Time: Life Beyond Sixty, Heilbrun expressed her desire to take her own life on her 70th birthday because "there is no joy in life past that point, only to experience the miserable endgame." She turned 70 in January 1996 and did not end her life.

She remained in good health with no known physical or mental ailments. One fall morning, after a walk with a close friend, she went home to her apartment where she lived with her husband. The next morning, she was found dead, having taken sleeping pills and placed a plastic bag over her head. She left a note, which read simply: "The journey is over. Love to all." Her son said she just felt her life was "completed". She was 77.

Extremely Old People I Have Known

I’ve seen people move out of their senior apartments because they ran out of money. Even if we successfully clear the financial hurdles of an epically long life, there are other risks.

I have met more people in their 80s, 90s, and beyond than most. I did so in the five years my wife and I acted as my mother’s caregiver. She had been living with us in our home as planned, but her mental health problems made it unbearable for all three of us. Very often, that’s the reason very old people end up in senior living apartments.

I went to every doctor appointment from 2015 until she died in 2022. I would not let anyone else substitute for me because I knew it was important that one person take notes and catch any mistakes that multiple doctors and hospitals make. There were a lot. Sometimes they would order a test that I would tell the doctor had already been taken, or tests missed that the doctor thought she’d already had. It’s not the fault of doctors and nurses. The number of patients they are required to see, and the limitations of the recordkeeping tools they are provided, make mistakes inevitable. Those tools are improving all the time, however.

Along the way, I learned much about gerontology. Did you know human taste buds don’t work well in old age? It’s true. My mother lived until age 98 and the last few years were brutal from a mental health outlook. Her physical health was remarkable all her doctors agreed but her resentment at having to live such a long life was palpable.

She was not the only one. I most vividly remember the 101-year-old who passed me in the hallway in the opposite direction of her senior apartment complex. This isn’t an assisted living facility. To live there, you have to be mobile and able to live without assistance. Meals and housekeeping were all that were provided. This centenarian, whom I did not know touched my forearm, looked me in the eye, and said: “Don’t wish for this” and then casually continued to make her way back to her room.

There were others, whom I knew well, who also let me know that a long life, even if in relatively good health isn’t for everyone. Mary, at the lunch table, once told me. “Sometimes I’m just ready to check out. Nothing’s fun anymore!”

I knew two other women living in this same facility who calmly told me they were doing their best to stop eating. They were impatient with God and just wanted to speed up the process, they said.

I understand that there are people that age and older who are perfectly happy to live past the age of 100. Dick Van Dyke, 99, recently said his current age can be the best time of life. Warren Buffett, 94, still works. But they don’t appear to me to be typical.

I would not and cannot, for religious reasons, do anything to shorten my life. I don’t even want to. I like that I am still useful in the service of family, friends and charities.

I do have a number in mind that I think would be the optimum age to die, but I won’t say it out loud. Emmanuel did and it didn’t go over well with his family. I don’t even claim, as Ezekiel does, that I will turn down medical interventions that would lengthen my life after a certain age. It’s just that living too long looks a lot more likely and less desirable than dying a bit sooner than most people expect.

A great topic to continue over coffee sometime!